Owners Manual of Stained Glass Conservation

"What belongs to today, alas, is the folly of restoration. That work of the Pharisees troubles my joy; my eyes, given to admiration, are suddenly stricken .... They have killed certain of the stained glass windows that were among the most precious motives of the glory of Chartres." - Auguste Rodin - Cathedrals of France, 1914.

Rodin's lament refers to 19th century stained glass restorations which have always been severely criticized for the destruction they wrought upon medieval windows. But in the seventy-five years since it was uttered, the situation has not much changed. Many bright and beautiful windows have been lost in this century to wanton destruction, thoughtless and insensitive restoration, and sheer neglect. The blame for this must be shared by those who own the windows, as well as those who restore them; but it is a fault of unwitting ignorance, not of willfulness. Most people, including stained glass craftsmen, do not know how to approach historic stained glass, to repair it or to take care of it.

In an effort to remedy this sad state of affairs, we offer these guidelines for owners of stained glass windows, whether churches, municipalities, or individuals, to assist them in the care of their unique treasures.

I. Research and how to make use of itÂ

The first step in caring for old stained glass is to research your windows, to find out all you can about their manufacture and provenance. This is not an esoteric exercise. It serves at least two vital purposes: first of all, knowing the designer or manufacturer of the window is a key to determining its value, just as knowing the artist will indicate the value of a painting. Secondly, knowing the history of a window tends to stir affection in the hearts of those who see the window often. The once-anonymous window almost develops a personality and, like a friend, becomes more interesting and familiar. It may sound ridiculous to personify windows in this way, but it is actually vital to their restoration: an owner who cares about and is interested in his windows will try to preserve them. There is no reason to automatically assume that any window is worthless. There are many examples of seemingly worthless windows suddenly being discovered to be very valuable; the most common is Tiffany's work, which was given away in the decades after the close of his studio. Now it brings thousands of dollars on the art market.

The information you should look for includes the following: artist or studio; location and date of manufacture; if the window was moved, its original location; and the repairs and restorations it has undergone.

Look the windows over first to try to find a signature or mark. Many windows were signed by the studios that manufactured them, often including the city, and sometimes the date. This signature is usually - but not always - located in the lower right corner, often in a narrow border. Alternatively, the studio may have used a seal or a cypher, an insignia that has nothing to do with the window design. This was more common in European windows. For example, James Powell & Sons of Whitefriars, London, signed their windows with a small monk in a white cowl - a "White Friar." The Kempe Studio used a sheaf of wheat ... and later a medieval-looking tower in front of the sheaf ... for the firm's new name, Tower-Kempe.

Not all windows are signed, however. Many of Tiffany's windows - and most of La Farge's - bear no signature. This does not lessen their value, nor does it mean they are not authentic.

There are a number of avenues to explore for information on your windows. If the windows are known to be original to the building, look into municipal or county building department records. If your town does not have a building department, or if the records do not date back far enough, try the local library and the municipal or county historical society. Local newspapers can be an invaluable source, chronicling consecrations, weddings and disasters. Churches and public buildings usually have records of building expenditures, or vestry or council meeting minutes, which can indicate how much was paid for a window, to whom it was paid, and later repairs and restorations. If the building is a local or federal landmark, your State Historic Preservation Officer should be able to provide you with some information.

If the window is not original to the building, tracing its history may be more difficult if you do not know where it was originally located. For instance, if you are buying a window that is not in a building, a reputable auction house should be able to provide a provenance for the window, but a small antiques dealer may not. Also keep in mind that not all windows in American buildings were made in America; many were imported and information on them may be hard to trace.

If your building is a religious or public structure, those who use the building should be educated to the significance of the windows. There are many ways in which to do this. A small exhibition or storyboard of the windows and their history or iconography may be mounted in the lobby or vestibule, where people may view it at their leisure. Sermons may draw on the windows of a church to illustrate Biblical lessons. Lectures may be given in schools, libraries, and historical societies. When the public cares about preserving the windows, the funding required for restoration may be easier to secure.

II. Physical evaluation of conditionÂ

The next step is to evaluate the physical nature and condition of the window, to determine if repair or restoration is needed. To do this accurately, someone who deals professionally with stained glass should be contacted, preferably a conservation consultant, such as this firm, or stained glass conservator. If none is available, a craftsperson or historian of stained glass is the next best able to assist you. It is necessary, however, for the owner to be at least passingly familiar with the terms and materials:

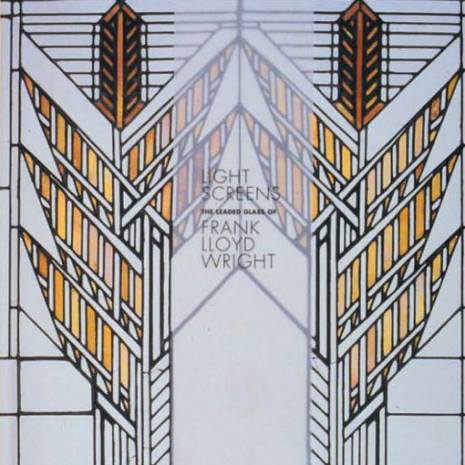

Glass

Here we must address the question that constantly perplexes the layman: What, exactly, is stained glass? On the most elementary level, stained glass windows are made of colored, painted glass: glass that is colored when molten, cut, decorated with vitreous paint, and assembled into a panel. On a slightly more complex level, stained glass windows may also be made only of colored glass, with no paint, or of clear glass decorated with colored paint, or of clear glass without paint, assembled in came.

There are essentially three types of glass used in stained glass windows.

- Antique glass (not named for its age, since it is still made today) is handblown glass. Its texture is uneven, with striations, bubbles, and varying thicknesses. This uneven quality imparts a radiance to the glass that machine-made glasses cannot equal.

- Machine-rolled or cathedral glass is evenly textured due to the machining process. This type of glass is commonly found in domestic windows.

- Opalescent glass is milky in appearance, with variegated colors and textures. It is commonly known for its use in Tiffany-type windows.

The issue of paint on windows also vexes the layman. To some, the idea that windows are painted connotes inferior quality or craftsmanship. This is misguided: since the invention of the craft in the Middle Ages, vitreous paint has been used to decorate, define, and enhance windows. It is still used today for the same purposes.

Another misapprehension about paint involves the coloration of the glass itself. It is commonly believed that the hues of colored glasses are imparted by an overall application of paint. This belief has led to the fear that colored glass fades in sunlight or with age. Both of these notions are false. All colored glasses are colored by the addition of metallic oxides to the molten glass in the pot, resulting in "pot-metal" glass. Thus the color is part of the glass; it cannot be separated or removed, and it cannot fade.

The process of painting on glass is similar to that of ceramic glazing. A vitreous paint is applied to the glass and fired in a kiln. When properly fired, the surface of the glass melts slightly to fuse with the molten paint, forming a bond that is virtually unbreakable. However, due to variables in paint composition and firing times and temperatures, that bond is not always completely formed. This results in flaking, which is extremely common in American windows.

Cames

Stained glass windows are made by joining pieces of glass into panels. The element generally used to join the glass is called "came." Traditionally, came was made of lead milled or cast in an H-profile. Lead came is still commonly used, as well as brass and zinc. The came, which is available in a wide variety of profiles, is shaped around the pieces of glass and soldered at the intersections on both sides of the panel. Putty is applied under the cames to make the window weather-tight.

Another method of joining the pieces is copper foil. This thin adhesive-backed foil is wrapped around the perimeter of the glass and the length of the seam is soldered. This is used in lamps, and is also found in many intricate opalescent windows.

Support system

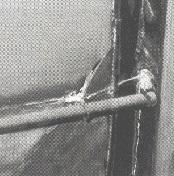

Although came is the primary support for a stained glass window, lead and copper foil alone are not strong enough to support an entire window. For this reason, support bars are used for lateral bracing and to bear the weight of individual panels. In windows, panels are often set on T-bars, which are set into the frame. In addition, saddle bars span the frame and reinforce the window. The panels are tied to the saddle bars with copper wire that has been soldered to the panel. Both types of bar are usually made of iron or steel.

Frames

Window frames can be made of wood, stone, or metal (usually steel or aluminum). Stained glass is also found in operable frames - double-hung, casement, or pivoting ventilator frames.

III. Deterioration

Only a trained professional can accurately determine the extent of deterioration in a stained glass window and the measures necessary for correcting it. However, there are a few things the owner should be aware of which indicate that restoration or repair work is needed.

Glass

Breakage, cracks, and missing pieces are a sure indication that the window needs repair. Also look for light leaks between the glass and the cames. These will appear when putty is gone and the glass is sagging away from the cames. Check for flaking fired paint. Do not remove flakes by touching or rubbing them; even old flaking paint is a vital and historic part of a window and its presence is necessary for the restoration of the decoration.

Cames

Metals used in cames are subject to corrosion and decay. If the cames are lead, look for a white powdery surface, or for cracks in the came. Do not try to move or bend the came, or to scrape the powder away; this will only weaken already fragile leads. Check all cames and foil for broken solder joints. If the came is zinc, look for holes and pitting.

Support system

An inadequate support system is the most common cause of damage in windows. If improperly supported, a window will sag and bulge, creating stress which causes the glass and cames to break. Look for bulges in your windows. If they are present, your windows may be in serious trouble. It is a common misconception that windows were designed to bulge. This is absolutely not true.

IV. Contact a specialistÂ

So now you have looked your windows over and discovered there are a few problems. What is your next step? Contact a conservation consultant or someone trained in stained glass conservation to come and look at the windows and help you review your alternatives. This step is very important. Just as you would get advice on how to restore your building, you must get advice on how to restore your window. Every single window is different; our firm can provide you with the advice, specifications, studio selection and supervision of the work you need.

V. Restoration

For each part of the window, there are points of restoration policy of which the owner should be aware before soliciting bids from craftspeople. In general, as much original material as possible (especially glass) should be retained. Restoration must retain the structural and artistic integrity of the windows, and interfere with the materials as little as possible. All restoration procedures should be reversible; that is, they must be able to be undone without harm to the windows. Replacement of damaged windows is not considered restoration.

Glass

Replacement of broken glass or of glass whose paint is unstable should be avoided if at all possible. There are methods for rejoining broken glass with a minimum of interference with the aesthetic of the window. These methods involve a refined technique of copper foiling or the use of an adhesive. These should be practiced only by qualified craftspeople. Painted details that have been lost should never be replaced on the actual piece of glass either in fired paint or cold (unfired) paint, but on a clear glass plate that is attached to the window with came or foil. Retention of painted pieces is particularly important in faces, hands, feet, and inscriptions even if they are broken. To discard these elements would be similar to cutting out a section of a painting that was damaged.

If glass is missing, new glass should match the old in color, texture, and thickness. Newly painted decoration should replicate the old decoration exactly in color and application. The style must be that of the original artist, not of the restorer. All replacement pieces should be signed and dated with diamond scribe beneath the cames.

Cames

Lead came often must be replaced because it is too deteriorated to save. When a panel must be releaded, the new came should match the old precisely in every dimension and in profile. This is also true if cames of other materials require replacement. Whenever a window is releaded, new putty is applied beneath the cames to seal the window.

Support system

Additional saddle bars may be necessary to keep your window from sagging. These should be the same dimension and shape as the originals, and should be tied or soldered to the panels. If they are of iron or steel, they should be painted with corrosion-inhibiting paint. Flat bars soldered to the panel should be avoided, since they can tear the came.

Frames

Wood or steel frames must be painted. If the frame must be replaced, the new frame must be able to support the weight of the window without requiring the destruction of glass to fit the panel into the frame. In wooden frames, the molding profiles should match the original. Many times steel frames are replaced with aluminum, because it is non-corroding. This is not advisable. Aluminum, which is not as strong as iron or steel, requires a larger cross-section to support the panel. This wider section necessitates the removal of borders, or other parts of the window, to accommodate its width, causing damage to the window.

VI. Solicit bids

With the help of your consultant, solicit bids from several studios. Many studios offer restoration and repair and the consultant will assist in determining studios' capabilities. Do not be deceived into thinking that the craft is a "dying art". Be advised that virtually anyone can call himself a restorer. There is no accreditation for stained glass conservation and restoration, so a craftperson's work must speak for itself. Have a representative of each studio come to see the windows and explain to you and your consultant how he will fix them. Your consultant should be able to gauge if he is on line with proper conservation procedure. Obtain a list of previous restorations and references from each studio, and follow these up. Go with your consultant to examine their previous work. Talk to their clients. Ask them how the studio respected their needs, how well they fulfilled their contract, how they were to work with in general, if the estimate compared favorably with the final cost, and if the client was pleased with the result. Most important, keep in mind that restoration is an expensive undertaking and the lowest bid may not necessarily be the best buy.

VII. ProtectionÂ

One of the most problematic issues in stained glass conservation is the external protection of windows from the elements and from vandalism. It is complicated by the need for energy conservation.

Wire mesh is often used in Europe, but it protects windows only from vandalism, not from the weather, and it does nothing for energy conservation. The favored method in the United States is some form of glazing. There are many alternatives here, in materials and in style. All glazing, though, should be external, unless interior vandalism is a concern. Glass or polycarbonate sheet (Lexan®) can be used. Polycarbonate sheet will not break on impact, and is therefore an excellent choice if vandalism is a major concern (as in cemeteries). Its major drawback is its appearance: the overall sheet obscures the stained glass with reflections and makes the building appear "blind." Glass can be used in sheet (plate) form, or in leaded panels. These provide a deterrent to vandalism, but cannot be said to be foolproof in that regard. Leaded protective panels generally have the best appearance, and may be necessary for landmark buildings, but they are also the most expensive.

The major issue of protective glazing, however, is not how it looks. Its purpose is first to protect the windows and second to be energy conserving. This is generally difficult to achieve because all protective glazing must be ventilated. It is impossible to obtain an airtight seal on a stained glass window. Because of this, air that enters the cavity between the stained glass and protective glass must be allowed an easy exit. This is to prevent the buildup of condensation between the glasses, which, aside from being visually disruptive, is extremely detrimental to a stained glass window. It is essential that the air between the glasses be allowed to circulate.

There is no formula for the design of ventilation outlets in protective glazing. Each installation has a unique set of conditions that must be considered. These include the materials of the frames and the building, the yearly relative humidity and temperature variations, the type of heating in the building, and the rate of expansion of the materials of the two glazing systems. Careful consideration of the design and installation of protective glazing is required for every building.

VIII. Photographic inventories

Before any work is done on your windows, arrange to have a complete photographic inventory made throughout the restoration. This is essential as a record of what was done. All photographs should be made in color transparencies as well as in black-and-white prints (contact sheets are generally sufficient), in reflected light and transmitted light (i.e., with the light in front of the windows, as well as with the light behind the windows). A schedule should be maintained to get photographs at the following stages:

- overall shots before the windows are removed

- each panel upon removal, before any restoration is done

- in the studio, selected shots of ongoing restoration and significant details

- each panel after restoration is completed, but before reinstallation

- overall views after reinstallation

These photographs should be kept by the owners - and handed over with the property or the windows if they are sold.

IX. Maintenance

Stained glass windows, like anything else, need periodic maintenance. Yearly inspection by the building owner and three- to five-year periodic inspections by a stained glass specialist should be arranged. Moveable panels - those in doors and operable windows - should be inspected more often, since they are subject to the most damage. Your stained glass consultant should become to you what your plumber or doctor is. His/her name should be kept on file, ready to be called upon when inspection time comes around or for emergencies. The building owner should keep records of inspections: when they were conducted, by whom, what conditions were noted, and how these conditions were addressed. Specific product names should be listed whenever work is done. Care of your windows should be as important as painting your house.

Window frames must be carefully maintained. Wood, iron, and steel frames should be painted regularly to inhibit corrosion, with great care taken to not get paint on the glass. Stone frames should be repainted when necessary. Operable vents must be kept working smoothly. They should not have to be tugged open or slammed shut, and should not open or close with a bang. These stresses will cause glass to break.

If your windows leak, your stained glass specialist should be called. Never let a layman - a carpenter, roofer, or the local handyman - try to repair them. Tar, paint, and bathroom caulk are forbidden as interim repairs. If your windows leak that badly, they should be repaired immediately by a professional stained glass craftsperson.

X. ConclusionÂ

Your stained glass windows are unique treasures that enliven your building and add interest and prestige. They should be cared for with pride and respect. With proper care, they will last for centuries, like their medieval forebears, and speak with eloquence of our era. They are historical documents, just as buildings are, and they must be preserved for future generations.