The Rivalry Between Louis Comfort Tiffany and John La Farge - Part 3

Fig. 4. Hall, Louis Comfort Tiffany Apartment, Bella Apartments, 48 E. 26th Street, New York, c. 1881. Louis Comfort Tiffany. G.W. Sheldon, Artistic Houses New York: D. Appleton, 1883 1884). Note the stained glass window on the right.

Another incident that may have added fuel to the fire was a contract written by Louis Tiffany in March, 1881, a month after his patent was granted, with Louis Heidt, one of the Brooklyn glassmakers with whose flint glass factory both artists had been working since the mid-1870s to obtain the opalescent glass for their windows.

Opalescent glass was still custom-made under an artist's direction in 1881 and Heidt was one of only three or four known glassmakers from whom Tiffany and La Farge obtained the materials for their early windows. This contract bound Heidt to sell his entire output of glass only to Louis C. Tiffany & pany for one year, renewable.10 Although there is no evidence that the contract was ever renewed, it effectively denied La Farge access to one of the principal sources of opalescent glass and probably hurt his business at a time when he had many large commissions to fulfill for clients like the Vanderbilts.

By 1882, there are indications that a legal battle had been launched. Searches of court records in New York City, Morris County, New Jersey (where Tiffany may have filed suit), and elsewhere have not yet resulted in locating any mention of an actual lawsuit.11However, correspondence concerning a lawsuit between the artists does exist, and provides the only concrete evidence that it was La Farge who sued Tiffany. In September 1882, Thomas Gaffield, a retired glassmaker who kept a journal of the glass industry, engaged in correspondence with the New York law firm of Betts, Atterbury, & Betts on the question of the first use of opalescent glass in windows. The attorneys asked Garfield, "in relation to a patent suit of ours, whether or not you have yourself used or known to be used by others opalescent glass, in the construction of panes and sashes for windows."12 Gaffield responded that John La Farge and Louis Comfort Tiffany were the ones he knew of.13 In response to Gaffield's request for more information, the firm stated that they were working in counsel with the law firm of DeForest & Weeks for Tiffany in defense of a suit brought by La Farge for infringement of his patent. Their aim was to have the patent set aside and to make "the path of art in this as in other directions free and unobstructed to all."14 Gaffield's response does not survive, but Betts, Atterbury & Betts' final communication with Gaffield does. By the end of September, two weeks after their initial letter to Gaffield, the attorneys state that their response to the suit must be filed by the following week and that they had located some manufacturers and glass dealers who they felt could provide suitable information to defeat the patent.15 Although it does not appear that the papers were ever filed, this correspondence clearly places the date of the suit in the fall of 1882.

The precise outcome of the dispute is unknown. It appears that it was settled, abandoned, or vacated by 1883. Both artists' reticence to push the argument further suggests that Tiffany and La Farge came to some mutual agreement allowing both to pursue their art. There is no record in the Patent Office that either patent was invalidated. By this time, competition from other artists had increased. Opalescent glass factories had opened to produce the material in quantity, making it easier for anyone to make stained glass windows. The ubiquity of Tiffany's process and La Farge's glass was such that, by 1883, Alphonse Friedrick, a Brooklyn stained glass maker, even patented a lead came of double height to aid in building layered windows, which his patent described in terms suggesting that the practice was common.16 There were more and more artists and craftsmen using the process, and to defend the patent from one, it would have been necessary to defend it from all, which would have been prohibitively expensive. Therefore, the patent argument may have been abandoned due to the sheer impossibility of defending it.

The tenor of the relationship between Tiffany and La Farge is observable in the articles of the period that chronicled their work. In the early 1880s, it was La Farge who was clearly recognized as the first to use opalescent glass in stained glass windows. The first published mention of it appeared in the New York Herald in November, 1879, describing La Farge's Derby window (Fig. 3)17 Despite the fact that Tiffany was experimenting with stained glass windows in the late 1870s, he did not receive media attention for them until a year after La Farge did, in November, 1880, the same month in which he applied for his patent. The New York Times ran an editorial stating that "Mr. Louis C. Tiffany has finished a window in stained glass which bids fair to mark an epoch in the United States in a new art industry."18 While this article lauded the window, it did not call Tiffany the first to use this glass. One month later, another Times editorial described La Farge's commission for the home of Darius Ogden Mills in New York, calling La Farge "one of the first, if not absolutely the first, to devote himself' to the solution of problems" in stained glass.19

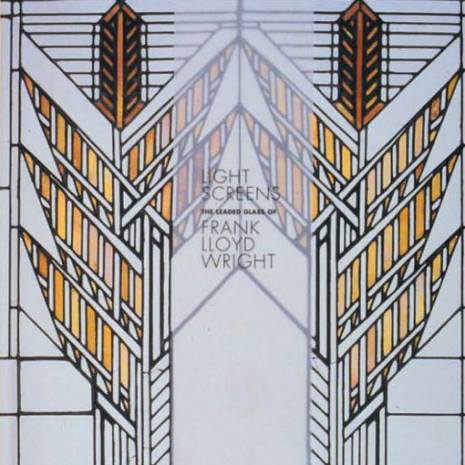

Fig. 5. Louis Comfort Tiffany, opalescent window made for his apartment in the Bella Apartments, c. 1880. 24" x 29". Private collection. Helga Photo Studio, courtesy of The Magazine Antiques.

The story that La Farge worked directly with glassmakers to produce glass to his liking was first related in the press in February, 1881. Tiffany would not make such claims for another decade. George Parsons Lathrop, working from notes provided by the artist, reported that "Mr. La Farge was also the first artist in America to manufacture glass to suit himself."20 For the next several months, most articles about American stained glass included the work of both artists, giving almost equal credit to both. From April to June, 1881, just after Tiffany received his patent, Roger Riordan (who had worked with both artists) published a three-part series called "American Stained Glass," in which he gave a balanced description of both artists' work and credited them equally for developments in both glass and artistry in windows.

At the same time, there was an increase in the number of articles about American stained glass naming artists other than La Farge and Tiffany. None of these articles is devoted exclusively to one or the other, and in some, neither is mentioned.21 Clearly, within less than two years of La Farge's Derby window, the use of opalescent glass in American stained glass windows was becoming widespread, despite Tiffany's and La Farge's patents. But where Tiffany's name was used, La Farge's was also found, suggesting the writers worked to antagonize or lionize neither, giving similar coverage to both.

In the fall of 1881, articles once again became devoted to one artist or the other but not both, led by reviews and notices of La Farge's exhibition of stained glass at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, a coup of recognition.

Tiffany had just received his patent.22 As favorable notices of La Farge's show began to appear in November, Tiffany appears to have launched an ambitious public relations campaign resulting in articles in which he began to assert his superiority to La Farge in both artistry and innovation.

The largest of these was the series of eleven articles called "From Lobby to Peak," begun in February, 1882, in which Donald G. Mitchell, writer and close friend of Tiffany's, described Tiffany's own apartment at the Bella on E. 26th Street in New York (Fig. 4 and 5).23 The articles were not merely descriptive, but also explained Tiffany's philosophy of decoration and included descriptions of several stained glass windows and uses of glass. Nevertheless, La Farge was riding a wave of great success and was further recognized in articles on his commissions for the William H. and Cornelius Vanderbilt houses and reviews of the exhibition at his studio of the Battle Window for Harvard's Memorial Hall (Fig. 6).24 The escalation of tone in the published responses to their work in 1882, which they were instrumental in placing, suggests that they were engaged in a stormy battle of some sort, if only for market share. La Farge must have initiated his suit around this time.

The rate of appearance of articles on either artist began to abate in 1883, after the suit had disappeared. The majority published that year were about La Farge.25 Perhaps with the lawsuit now out of the way, it became less important to both artists to pursue their fame in the newspapers. Mentions of La Farge's patent ceased after 1881, and Tiffany's patent was never mentioned in articles of this period. Tiffany did receive press attention about his interiors, such as the Seventh Regiment Armory (Fig. 7) and the Union League Club, where La Farge also provided windows and decorations. These articles rarely mentioned, let alone focused, on Tiffany's window designs, though. In 1884, few articles on the stained glass of either appeared. In fact, until 1889, the number of articles about stained glass in general and Tiffany or La Farge specifically was considerably less than in the years 1879 to 1882. Both artists experienced personal and financial difficulties in the mid-1880s. Despite repeated costly efforts between 1879 and 1885, Tiffany failed to establish a glass furnace of his own. His first wife, May Goddard, died in January of 1884. The following year he lost thousands of dollars in the financial failure of the Lyceum Theater, which he had decorated for a share of the profits instead of being paid. This coincided with La Farge's legal troubles over his decorating company, which culminated in his arrest for grand larceny of his own sketches (the charges were later dropped). These events suggest that both artists had less time to cultivate their images in the media or to develop their artwork.

Continue >>