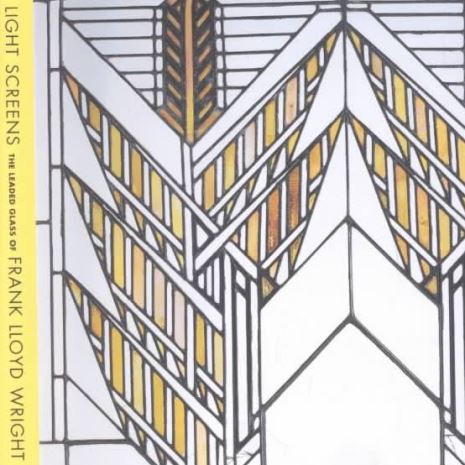

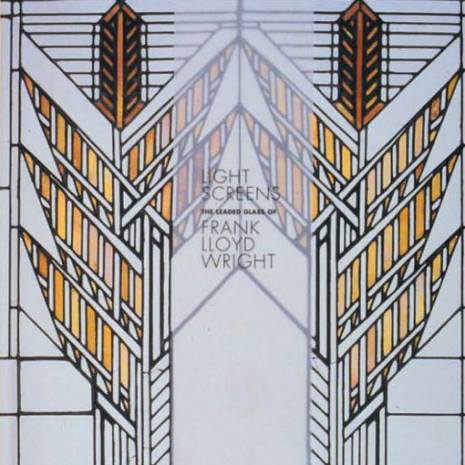

Light Screens

The Leaded Glass Windows of Frank Lloyd Wright

by Julie L. Sloan, LLC

Since 1982, Julie L. Sloan, LLC has been doing research on the leaded glass windows of Frank Lloyd Wright in preparation for a book manuscript. With the help of grants from the Graham Foundation for Advancement in the Fine Arts and Architecture and the National Endowment for the Arts, she has photographed the windows of over 40 of Wright's houses built between 1886 and 1923. In addition, she enjoys a close working relationship with the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation at Taliesin West and has done extensive research in Wright's own drawings for his decorative windows.

Frank Lloyd Wright, who has long been recognized as America's greatest architect, was also one of its most prolific stained glass designers. Working with leaded glass between 1886 and 1923, during a time when the popularity of stained glass had a reached a height not equaled since the Middle Ages, he designed over 150 houses that included leaded glass in virtually every window opening. If we estimate conservatively at thirty windows in a house, this amounts to more than 4,000 windows. This is a conservative estimate, however, since the Dana and Martin houses had over 200 windows each, and the second Little house more than 300. Of the 150 buildings Wright designed to include leaded glass, better than 90 were built. Sadly, 17 percent of them have been demolished and 20 percent more have lost at least some of their decorative windows.

red line

In many modern writings about Wright and his decorative windows, "art glass" is the preferred term. However, to the rest of the world, including Wright's, the term "art glass" was a derisive term indicating windows that were the opposite of their name - decidedly non-artistic, designed without regard for any particular architectural style, cranked out literally by the yard like wallpaper to meet a great demand for a low-cost, popular decorative form.

The term was coined and the item produced in the Midwest during the late 1880s, in conjunction with a building boom that spawned a retailing invention, the mail-order catalog. By 1910, mail-order catalogs like those from Sears Roebuck and Montgomery Ward offered "art glass" windows in every style, from Art Nouveau to Prairie to Gothic Revival. Art glass windows were executed in multiples, of cheap glass, and at little expense to decorate the bathrooms and stair-landings of row-houses, mill towns, and tenements around the country.

In contemporary writings about Frank Lloyd Wright's buildings and in Wright's own writings, including correspondence, specifications, and working drawings, the term "art glass" was rarely used. Instead, Wright's windows were almost universally called "leaded glass" by critics and by himself. Today, Wright enthusiasts often reject this term because of the erroneous belief that Wright's windows were all made with zinc came, not lead. First of all, this isn't true - many of Wright's windows were indeed assembled with lead came. More importantly, to craftsmen and glass historians, the term "leaded glass" is a generic one that does not define the metal of the cames in its use. The 1923 handbook published by the Pittsburgh Plate Glass Company demonstrates this. Next to a photograph of windows from Wright's Susan Lawrence Dana house, windows made with brass came, it says:

"`Leaded glass' is a term referring to a method of treatment, rather than to any particular kind of glass, or indeed, to any particular metal as a setting for it .... The term `leaded' does not signify, furthermore, that lead is of necessity the metal employed; harder metals, such as zinc and copper, also are used to a considerable extent."

Wright's own term for his windows was "light screens." In his Autobiography, he talks about " ... diffusion of reflected light for the upper story through the `light screens' that took the place of the walls and were now often the windows in long series." Light screens, however, is a somewhat cumbersome term, and so the term "leaded glass" is not an erroneous or misleading one to use in discussing Wright's ornamental windows.

Prior to 1895, Wright's architecture, and specifically his window designs, were firmly grounded in the vocabulary of the Queen Anne and Shingle styles. From 1886 until 1893, the young Wright served his apprenticeships, first with Joseph Lyman Silsbee and then with Louis Sullivan. It was not until 1893 that Wright became an independent architect. His first independent commission was the Winslow House in River Forest in that year. But three years earlier, he had built a house in Oak Park for his rapidly growing family. In it, the influence of the Queen Anne style is clearly visible, especially in the diamond-paned windows that are reminiscent of medieval domestic architecture.

In the Winslow house windows and in the dining room windows of his own house, done in 1892, Wright began to experiment in breaking away from Queen Anne window patterns by adapting a lotus design from an 1886 German window pattern book. Although Victorian in inspiration, it is a stepping stone to the Prairie window, to which Wright was able to leap directly in 1895 in his Studio office and reception room, which he added to his home in that year. Here the vocabulary of the Prairie window was born. The severe but complex windows and ceiling panels, some of the finest Wright ever designed, are completely without precedent in Wright's window designs. They set the stage for the next 25 years of Wright's decorative work. With these panels, Wright turned his back on his training in naturalism at the elbow of Louis Sullivan and declared himself the founder of a new style - the rectilinear Prairie Style. While it took a few more years for the style and its function to meld and mature in Wright's houses, the design vocabulary for the ornamentation of those houses was mature in 1895.

This is the point at which most stained glass designers stop. Having found a working vocabulary, they are content to explore it fully, but insularly, as a entity completely separate and divorced from the architecture. This can be clearly seen in the windows designed by Wright's contemporaries, Louis Comfort Tiffany and John La Farge.

But for Wright, the window pattern was not an end in itself. Without the functional integration of the window into the architecture, the ornament carried by the window meant little by itself. The fully realized Prairie window would incorporate the vocabulary of rectilinearity, earthen colors and areas through which to see with the functionality of the casement sash and strip fenestration to create an organic whole with the architecture.

In designing door and window openings, Wright had once bemoaned the "beautiful buildings I could build if only it were unnecessary to cut holes in them." The Prairie window resolved this difficulty for Wright. Now, no longer intimidated by the necessity of cutting holes in buildings, Wright took control over the fenestration of the house. Bands of windows - or strip fenestration - replaced the single hole-in-the-wall window and served the ornamental function friezes had in earlier houses, providing texture and visual interest in the shadows under the eaves. Where formerly Wright had toyed with the casement window in a few buildings, he now firmly established its precedence over the "poetry-crushing guillotine" double-hung window, which he categorically refused to use. The casement, which opens by means of hinges at the sides, like a door, was preferable because it brought the outside in more effectively than the double hung sash, in Wright's opinion.

Moreover, and critical to the success of Wright's ornamental window patterns, the casement window was a single panel from sill to lintel, uninterrupted by the meeting rails of the double hung sash. If these patterns had been executed in double-hung sash, the raising of the lower sash would superimpose its pattern on the upper sash, muddling the design and rendering it illegible. It is significant that in the few buildings in which Wright resorted to the double-hung sash, ornamental glass is found only in the stationary upper panels; the lower sashes are plain plate glass. Without the casement sash, Wright probably would not have developed the complex and intriguing ornamental patterns found in his windows. The single open expanse provided by the casement became the canvas - and light was the medium - for Wright to create ornament. Using the vocabulary conceived in his studio windows to enhance the fenestrational pattern, Wright created the Prairie Window.

By 1901, when the Frank Thomas house was built in Oak Park, the Prairie house was a full-fledged architectural system, in which Wright's principles of organic architecture were paramount. In organic architecture, ornament is essential, but its design is fundamentally related to that of the building. Wright asserted that "the element of pattern is made more cheaply and beautifully effective when introduced into the glass of the windows than in the use of any other medium that architecture has to offer .... " In many of his buildings, leaded glass windows are Wright's sole ornamental expression. In the Thomas house, Wright pulled out all the stops for their design, employing gold leaf, intricate leading, a combination of lead and zinc cames and a rich, possibly floral design in French doors and bands of casement windows around the house.

red line

The 1902-04 Susan Lawrence Dana house, in Springfield, IL, is one of Frank Lloyd Wright's architectural masterpieces. In terms of its glass design, it is unparalleled. The most ambitious of his executed Prairie houses, it is today all the more impressive because of its intact state, providing an incomparable experience of the Prairie house as Wright intended it. It is a house museum open to the public. With the luxury of a client to whom money was no object and who trusted her architect completely, Wright was given free rein for his architectural and ornamental expressions in this house.

Not least among its superlative qualities are its windows. Numbering over two hundred and fifty, the variety, complexity, color, and use of leaded glass in this house defies comparison. With these windows, Wright refined the elements of the Prairie window idiom into a symphony of light that remains unsurpassed. Using variations on several themes, each room has its own motif, united with the whole through an underlying harmony of color and design.

Some of the most representational of Wright's windows, the Dana house windows clearly depict the flora and fauna of the prairie - butterflies and sumac trees are easily identifiable in the glass patterns of the entry, the reception room, and the dining room.

The chevron pattern used in the Dana house became an important component of the design, executed usually in green or amber iridescent glass. This motif would recur in Wright's windows for several more years. It is found in the ceilings of the inglenooks and the dining room, the library, living room, master bedroom, and reception room windows.

The Dana house also contains Wright's most innovative and unique expressions in glass, never tried before and never used after. One of these is the butterfly lamp, the most ornate and beautiful of Wright's light fixtures. Another unique use of glass in the Dana house is a two-story pattern, found in the living room and the master bedroom above it. This is an especially unusual treatment, since it is fully legible only from the exterior, which is not the best vantage point from which to view leaded glass. There is no point inside the house from which both windows are visible.

The most unusual of Wright's expressions in glass is the glass "tapestry" in the gallery. Hanging in front of an arched plate glass window are nine separate panels of leaded glass that comprise the tapestry. Mindful of the structural stresses inherent in hanging glass, large areas of the tapestry are left open, unglazed, to lessen the weight.

red line

The house built for Darwin D. Martin in 1904-1905 in Buffalo, NY, was one of Wright's most ambitious. Today its effect is radically diminished, due to the erection of a nondescript apartment building in what used to be the Martin backyard, for which the pergola, conservatory, garage and greenhouse were demolished. In addition, the house itself has lost windows, furniture, and decorative treatments, and rooms have been rearranged. Restoration of the house is planned.

Two principle window patterns were designed for the Martin house, which, during construction, were referred to simply as the first and second floor patterns. Wright gave no specific titles to them. They are similar to the windows of the Dana house, incorporating similar motifs and the same materials. The main first floor pattern has been called `Wisteria' by historians, but Wright never referred to it in that way.

One of the most famous of Wright's windows is today called the "Tree of Life," but the origin of this name is unclear. While it stands as one of Wright's finest single designs, there is no indication of any special regard for it on the part of either Wright or Martin. The "Tree of Life" window, like the Coonley Playhouse windows, is often misinterpreted as an autonomous design, due to its presence and display in a number of museum and private collections. Viewing it as such is to miss the true significance of the design. Frank Lloyd Wright never intended any of his windows to be seen outside the architectural context for which they were designed. While the "Tree of Life" window does work successfully on its own as an autonomous piece, its impact in multiples in a room is more forceful. Wright intended the whole to be greater than the sum of its parts, an effect difficult to imitate in any museum setting; sadly, that effect is also now difficult to see in the Martin house itself, since most of these windows have been removed.

red line

The 1909 house built in Chicago for Frederick Robie is one of Wright's masterpieces of the Prairie period. As a prominent element of the house's ornamentation, the windows are some of Wright's best known. Robie himself claimed to play a large part in their creation.

Robie House, living room french doors. Robie House, living room french doors.

He said, "I wanted windows without curvatures and doodads, both inside and out. I wanted all the light I could get in the house, and shaded enough by overhanging eaves ... I wanted this room to be so that I could look out to the north and see down the street to my neighbors, without their being able to invade my privacy." And that is exactly what he got.

The windows of the Avery Coonley Playhouse are considered to be Frank Lloyd Wright's masterpiece in glass design. As a unique expression in glass, they are among his finest work in two dimensions. The original windows, all removed from the house in the late 1960s, can be seen in various museums around the world.

But they have too often been examined as autonomous works, divorced both from the location for which they were designed and from Wright's total work, doing a disservice both to Wright and to his creation. This misinterpretation has arisen as a result of their having been torn from the Coonley Playhouse and established in places of honor in museums and private collections, to be seen as autonomous objects representative of Wright's entire early period, rather than as part of a system of ornamentation for a specific and unique building. The forty or more Playhouse windows were designed as a pattern that continued around the room through the clerestory and small side triptychs to the large triptych at the front of the building as its focal point. Horizontal lines tie the individual sashes together compositionally, although not one design is repeated. This facet of the design is lost in displays of individual windows, but is hinted at in period photographs of the interior of the kindergarten.

With the Playhouse windows, for the first and only time in his window designs, Wright took his inspiration from an event - something having to do with balloons, either a parade or a passing balloon vendor - the story varies slightly with the teller. Using bright red, green, blue, orange, and black glass, colors not used before in his windows, Wright created what he called a "Kinder-Symphony."

Wright was particularly fond of this design. The sample panels were displayed in the 1914 Chicago Architectural Club exhibition, and he kept them in the studio at Taliesin near his drafting table. One of the designs was used by Taliesin Associated Architects as the marker for Wright's grave in Spring Green, Wisconsin, certainly an indication of the architect's fondness for the pattern, alone among all his thousands of other designs.

The design of the Los Angeles house for Aline Barnsdall, called the Hollyhock House, was commissioned in 1917, although construction was not begun until 1920. This building is now part of the Los Angeles County Museum and is open to the public. The hollyhock theme was the client's suggestion. This floral theme was used to decorate the flat exterior walls, and carried indoors and executed in the furnishings and ornamentation, including the windows. The living room, library and music room space is the focal point of the house. In these rooms, large doors of plain plate glass open to the terraces, pool, loggia and garden courtyard. The doors are flanked by narrow sidelights of ornamental glass in a dancing triangle pattern in purple, green, and white, set in copper-plated zinc.

One of the unusual aspects of the house and its windows is the purple and green color scheme. In letters to Wright, Barnsdall discussed this several times. Describing the living room as she wanted it, she mentioned that, "this section was to have a wood treatment of untouched walnut - combined with the soft purple I showed you in your Japanese prints - and a touch of gold to link it with the screens" that were to be built into the walls of the living room.

The most dramatic space of the house, and one of the most exceptional in any of Wright's houses, is the glass porch off the nursery. It is a purely ornamental conceit in glass - the French doors open upon a one-story drop to the lawn, the space is too small to furnish, and it must be reached by passing through the nursery, usually a very private space. The three glass walls of this jewelbox make it at once frivolous yet serene. Whether the porch was Wright's idea or Barnsdall's, its uselessness is unlike Wright, but its beauty for beauty's sake is a refreshing break from his usual seriousness.

Frank Lloyd Wright's last designs for leaded glass were for the textile block houses in Los Angeles. Of these, only the Charles Ennis house was glazed with leaded glass, in 1923. Wright's specific reasons for discontinuing the use of leaded glass in his buildings are unknown. Certainly, societal inclinations were leaning away from any type of ornament towards Bauhaus and International Style minimalism - and owners were no longer interested in tolerating the drafts and upkeep problems common to leaded glass windows. However, it is difficult to point to any one of these as reasons for Wright's discontinuance of its use.

His cessation of the use of leaded glass did not indicate a lessening of his interest in ornamental patterns in glass. In a number of buildings executed in and after the 1920s, Wright employed highly innovative techniques in glass. In the 1920s, pattern was executed in windows with wood mullions instead of lead and zinc in both the Jiyu Gakuen school in Tokyo in 1921, and at Taliesin in 1925. In the 1930s, the use of Pyrex tubing as windows, their patterns created by the joiners, was a highly unique glazing approach in the Johnson Wax Administration Building in Racine, Wisconsin. With the invention of the Usonian house in the 1940s, window patterns were created by perforating plywood panels and sandwiching plate glass between them. Until the end of his life in 1959, Wright was fascinated with fenestration and the manipulation of light in the interior, and deployed the windows of his houses with great deliberation, skill, and originality.

Since Wright never wrote much about leaded glass, his reasons for its use and discontinuation of that use will probably never be completely understood. The windows of over 150 houses and projects were designed by Frank Lloyd Wright and his studio. For one whose life's work is in stained glass, this would constitute a stunning output. For an architect whose design responsibilities were obviously not limited to windows and who ceased using leaded glass only halfway into his career, they are one more indication of his prolific genius.

The above is the text of a 20-minute or one-hour slide lecture that the author has often given.

To book this lecture, or any others, please contact Julie L. Sloan, LLC.